Dentine hypersensitivity: Diagnosis for a better dentist-patient relationship

Getting mouthy about sensitivity

Making a proactive diagnosis of dentine hypersensitivity could help strengthen the dental healthcare profession-patient relationship. This may be particularly relevant in an era of remote consultations. A simple question asking if patients ever play with their food in their mouth could be a springboard to create an opportunity to take a wider look at what oral health means to them.

Think small, not big

Are dentists overlooking an easy opening to improve patient engagement? Dr Koula Asimakopoulou, Reader in Health Psychology at King’s College London, believes they could be: “Dentine hypersensitivity is a huge, huge opportunity for dentists to show they have a genuine interest in the patient - even in their small niggles - that might be troubling them, rather than the big, big issues.”

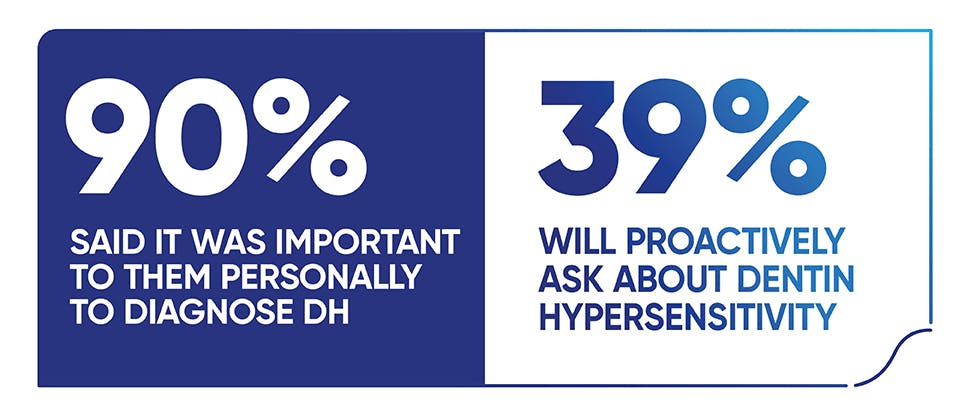

In research among dentists, 9 out of 10 said it was important to them personally to diagnose dentine hypersensitivity (DH) in their patients.1 Yet, just 39% will proactively ask about DH.1

Professor Barry Gibson, Professor in Medical Sociology, School of Clinical Dentistry at the University of Sheffield agrees that being proactive in asking patients about DH can have wider benefits: “Dentists who show care and attention to dentine hypersensitivity are demonstrating care for these patients and will be making it easier for them to come and seek support when they need it. They will remember this later and they're going to regard this positively.”

Building a better patient relationship brings clear personal positives for dentists too. In a survey, 99% of dentists said creating and maintaining good patient relationships had often or somewhat improved patient satisfaction, 93% said it had often or somewhat improved clinical outcomes and 97% that it had improved patient visit rates.1

It’s not just in their heads

Taking a proactive approach and asking about DH is an example of the new ethics of care, a growing concept in sociology. As Professor Gibson explains: “A good dentist is someone who demonstrates this kind of ethics of care, who shows care and attention and focuses on the patient as an individual. If a patient comes in with sensitivity and you don't show care and attention to that, then is that really going to be something that the patient kind of picks up later, should there be progression.”

Asking about DH allows the dentist to partner with the patient as they go through the dental journey of their lives. “When the dentist legitimises their dentine hypersensitivity, it gives it importance by one: paying attention to its existence; two: normalising it; and three: then offering a solution,” says Dr Asimakopoulou. “That sort of talk is going to be particularly helpful to the patient as it establishes that they are not imagining things, it’s not in their head, it is a problem that has a physical root to it and it is one that is worthy of the dentist’s time and attention.”

This is backed up with research that shows that patients’ perceptions of the quality of dental care, and the likelihood of them seeking dental support, are related to their perceptions of dentists as caregivers.2 For patients, dentists that inform them about treatment options and their communication skills are among the perceived characteristics that are likely to improve their satisfaction levels.2

“The talk of dentine hypersensitivity as a kind of non-condition or a condition that is non-real, … or not important - that talk is actually closing down a real opportunity to engage.”

It’s all about them

Creating a patient-centred approach is important. Research has found there are five components essential in aiding a patient-centred approach; without these patients are less satisfied, less enabled, and may suffer greater symptom burden:3

- Communication and partnership (a sympathetic healthcare professional interested in patients' worries and expectations and who discusses and agrees the problem and treatment)

- Personal relationship (a healthcare professional who knows the patient and their emotional needs)

- Health promotion

- Positive approach (being definite about the problem and when it would settle)

- Interest in the effect on the patient's life.

Dental research found that personalising the patient-dentist connection goes beyond what is happening in the mouth. Dentists themselves said that talking about family life or work, sharing their own personal experiences and taking the time to talk and listen to the patient all help build this relationship.1

DH can offer dentists a chance to open up a more personal conversation with patients. Professor Gibson points out: “I think that the talk of dentine hypersensitivity as a kind of non-condition or a condition that is non-real, as it were, or not important - that talk is actually closing down a real opportunity to engage. The conversation closes at that moment for so many patients. ‘It's just hypersensitivity, think of a sensitive toothpaste’, without showing the care and developing that more elaborate conversation.”

Dr Asimakopoulou recognises that asking about DH may require a shift in current behaviour. “Dentists may need to be supported here in terms of giving help to actually fit in questions about DH in their normal routine. So that asking about DH is normal, it’s easy and it’s acceptable. To not do that is somehow the odd behaviour, if you like.”

Of course, DH might not be an issue for many patients. Although it is accepted that one in three patients have DH, there may be more patients affected as not every patient may feel that it is a particular issue for them or that it is worth raising with their dentist.4

That’s why asking about DH as a standard question is important believes Dr Asimakopoulou. “It’s really about being patient centred and being led by the patient. Just because a patient says, ‘no thank you, I don’t want to talk about this particular issue’, doesn’t mean you must never talk to them about it.”

We’ve never been closer, even at a distance

Professor Gibson highlights a unique communication dynamic within the dental practice. “There is a hierarchy in dental practice between look and feel. So you as a patient feel things, but the dentist looks. And the looking is more important than the feeling.”

With the increasing move towards remote telephone and online interactions, this hierarchy has been upended. However, Dr Asimakopoulou believes it creates an unparalleled opportunity for dentists: “I think the dentist will have to think about intervening through their communication skills.”

She adds that undertaking clinic work while wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) can hamper the usual face-to-face interaction. “In contrast, online or telephone conversations should be really easy because there is no PPE to interfere and the same broad principles that dentists use in face-to-face consultations also apply online. This is probably an opportunity to deliver really good care whilst building this ongoing rapport with patients.”

DH is an ideal fit for a remote consultation. “It’s an easy condition to ask about. It’s something that a lot of people have so you can normalise and be upfront about that. And it’s a condition that is easy to fix. Patients do not need to do really complex lifestyle changes that they have to deal with, all they really have to do is use the right toothpaste,” says Dr Asimakopoulou.

It also feeds into a praise and reward loop for the patient. As many patients have already changed their behaviour to cope with their DH, they can be congratulated for doing “the difficult bits”, she adds. “A dentist who shows they care, and they are empathic about simple behaviour change, is probably in a better place to tackle more complex changes further down the line because they will have a better relationship with their patients.”

Do you ‘mouth play’?

Taking the time to talk about DH in a consultation can be easy, which helps to then embed this within an everyday routine. One suggestion from Professor Gibson is to ask patients about ‘mouth play’, once the subject of DH is open, as a means of probing whether they have sensitivity. Data revealed that 80% of people surveyed reported ‘mouth play’, where they moved food around in their mouths to avoid certain teeth.5,6

“To show care and attention, ask about mouth play. ‘Do you play with food in your mouth, do you avoid certain parts of your mouth? Tell me more about that.’ Ask open questions and allow the patient to talk about that and encourage them to do so,” he recommends.

Using the Dental Health Experience Questionnaire (DHEQ) then allows dentists to explore this in more depth. Although this is designed to measure change, says Professor Gibson, it can be used as a benchmark of how DH progresses and could be used as a tool to aid discussions. Click here to register/sign in to access and download the DHEQ for use in practice.

Of course, this should fit within the broader principles of patient communication. Dr Asimakopoulou advises opening a consultation by asking open questions, setting an agenda, dealing with the patient’s agenda, summarising actions and setting smart goals that have been jointly negotiated.

She adds that these basic principles also apply when doing remote consultations. She has one final piece of reassurance for those dentists worried about this new world of communication. “They have had practice in communicating longer than they have been practising dentistry!”.

Start the journey

Being proactive in diagnosing DH in patients can not only foster a patient-centric approach to practice, it can be a means of demonstrating an ethics of care. This in turn can build on-going relationships that last.

With the move to non-face-to-face consultations, DH can also provide an easy opening for the dentist to showcase the wider aspects of their preventative dentistry ethos.

As Dr Asimakopoulou says: “It’s important to actually understand the patient’s health and illness journey and really to treat them holistically as a human being.”

Communication skills basics7,8

- Active listening – and use open, not closed questions.

- Empathise.

- Explain using non-jargon, easily understood language, e.g. sensitive teeth, rather than dentine hypersensitivity. Be aware that patients that are less bothered by their symptoms do not regard themselves as having sensitivity.9 Instead, asking about triggers, such as hot/cold drinks, that cause any sensation in their teeth, may be something that elicits a response.

- Clarify information and check that the patient understands.

- Use short sentences containing words with few syllables that are easier to understand than sentences containing many polysyllabic words.

- Make sentences more understandable.

- Provide reassurance.

- Tell the patient the important points first – and tell them that these are the important points and repeat if necessary.

- Be specific, not general.

- Non-verbal aspects are important, and these can be enhanced in a remote consultation, e.g. body language, facial expression, posture, gesture, and para-language, e.g. tone, pitch, ‘ums’ and ‘ers’. Some 93% of communication skills are non-verbal, just 7% is verbal.