Understanding the Patient Psychology of Dentin Hypersensitivity

Do patients and dentists think dentin hypersensitivity is a minor oral health issue or a chronic condition?

Insight from wider sociological and psychological work suggests changing the perception of dentin hypersensitivity could help patients manage this common oral complaint and also help strengthen the dentist-patient relationship.

Is it time to think differently about dentine hypersensitivity?

Dentine hypersensitivity (DH) is estimated to affect 1 in 3 people.1 Its ubiquity as a condition can mean that it is regarded, by both patients and dental practitioners, as a minor oral health concern. Yet, even among those with mild symptoms, coping measures to manage DH can affect their daily activities.

“We know that the impact of this condition can, for some people, result in really significant impacts on oral health related quality of life,” says Professor Barry Gibson, Professor in Medical Sociology, School of Clinical Dentistry at the University of Sheffield. He added that how DH affects people can range from being very mild to becoming predictable and forming part of an “illness career.”

Does this provide dentists with an opportunity to reappraise DH? “Seeing it as a chronic condition means that the dentist can see that this may well have progression. This could be something that could be long term and that needs management,” adds Professor Gibson.

Understanding this health and illness journey is vital and can have longer-term benefits for the dentist-patient interaction that goes beyond the time they spend in the dentist’s chair. Recognising the impact a simple dental condition can have on patients’ real lives outside the surgery can help change the interaction between them and their dentist, believes Dr Koula Asimakopoulou, Reader in Health Psychology at King’s College London: “It’s about building a relationship, using the easy, the simple and the mild - and fixing these - to actually engender trust and confidence in the relationship with the patient.”

“We know that the impact of this condition can, for some people, result in really significant impacts on oral health related quality of life”

It’s not major – but it matters

Research from Professor Gibson’s team suggests that DH has over the years been “displaced, trivialised and transformed into a non-problem problem”.2 Although this has been the necessary consequence of an essential public health focus on caries, he points out that now we are seeing conditions arising as a direct consequence of improved oral care, such as dentine hypersensitivity from over brushing.

From the dentists’ perspective, DH is a commonly seen condition. In GSK research among dentists worldwide, 45% make a DH diagnosis at least once daily.3 Patients who are less concerned about their DH are, unsurprisingly, less likely to seek dental advice: 42% versus 82% of those that are highly bothered.4 Yet, even among those patients who are less bothered about DH, nearly half will experience symptoms at least once a month, while over a third suffer weekly.5

Although this DH experience is broadly similar to those that are highly bothered, these ‘mild’ sufferers tend not to categorise themselves as being someone with sensitivity or having ‘a condition’, they simply experience sensitivity occasionally and have found ways to cope with it by making lifestyle adjustments.6,7 But why should they? Professor Gibson believes dentists could be missing an opportunity to engage with a significant sector of their patient population: “Many participants [in our research] indicated that they felt dentine hypersensitivity was actually part of their life”.

It’s a chronic complaint but…

This emphasises the fact that DH is a chronic complaint. “I can tell you from the classic sociological literature on this, dentine hypersensitivity certainly fits the picture as a chronic condition,” confirms Professor Gibson.

DH can alter the way patients act, restrict their eating habits, cause them to make adaptations to daily life and affect their social interactions, as well as having an emotional impact and affecting their personal identity.8

Professor Gibson acknowledges that one of the issues is a lack of understanding around DH progression. “But it can and for many people it definitely has done. And when it does, it has really significant impacts on everyday life.”

…why don’t people complain?

Put simply, people with DH have already learned to cope, even those that say they are less concerned have changed their lifestyle to manage the condition.9

“One of the fundamental indicators that you have a chronic condition is restrictions, limitations to the performance of daily tasks. Dentists and patients who don't take the condition very seriously, it's because they've adapted so quickly because pain forces you to adapt,” explains Professor Gibson.

Capturing the nuances of DH’s impact on quality of life has resulted in the development of the Dentine Hypersensitivity Experience Questionnaire (DHEQ), which is a validated, condition-specific measure used to evaluate responsiveness to change in oral health-related quality of life measures in DH patients.10,11

Research utilising the DHEQ has found that among patients with DH, these adaptive behaviors fall into four categories:10,12

The condition also has an emotional impact. In research, 89% found DH annoying, while a similar proportion found it irritating.10,12

“Dentine hypersensitivity requires a range of adaptive behaviours to avoid pain and sensitivity,” explains Professor Gibson.

I’m fine – I can live without a hot cup of tea

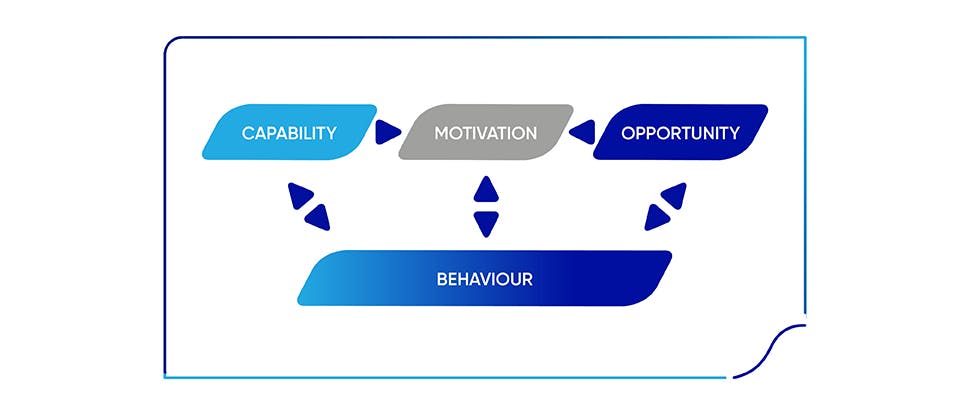

“We use the COM-B model of behaviour change* to talk about capability, opportunity and motivation. These people will be ticking all three boxes for behaviour change. Only in this case, their apparent success in the short-term in solving the problem will probably mean they are less likely to want to engage with the dentist to deal with the problem in the long-term, unless the dentist brings it up and if the dentist offers a really easy solution.”

Who raises the issue could be a factor. Recent GSK research among dentists worldwide found 53% believed it was their role to raise DH with their patients.3

However, once raised the “easy solution” that Dr Asimakopoulou refers to could simply be met by recommending a dentine hypersensitivity toothpaste. Daily use of a sensitivity toothpaste can significantly improve the quality of life impact of DH after 8 weeks, in particular the emotional impact, the restrictions around their eating habits and how they change their habits.10-12

*The COM-B model of behaviour is widely used to identify what needs to change in order for a behaviour change intervention to be effective. This will occur only when the person concerned has the capability (C) and opportunity (O) to engage in the behaviour and is more motivated (M) to enact that behaviour (B) than any other behaviours.

Figure: COM-B model of behaviour change (adapted from Michie, et al, 2011)13

Let’s talk about the ‘S’ word

For the dental practitioner, being more DH-aware can make a significant difference to their patients. Dr Asimakopoulou believes DH offers dentists a chance to engage with the patient on a simple behaviour change model. “DH is a brilliant opportunity to do that. So, there is a problem, there is a solution in the toothpaste you are suggesting to the patient and that will make the problem more manageable. I think DH provides an opportunity for dentists to be associated with success in behaviour change.”

However, research suggests that time may be a factor for dentists in raising issues, such as DH: 31% of dentists say they don’t spend enough time understanding patients’ oral health behaviours and around one in four say they have not spent sufficient time offering advice on these behaviours.3

Failing to engage with DH, however, sends a clear message to the patient. “A dentist who is dismissive about a mild condition essentially gives the patient the message that the condition is not important, it’s not worth their time and attention and the patient shouldn’t be concerned with it. We know that, in that case, the condition will go on in the background and it won’t just disappear overnight, and it will remain a niggle rather than a huge major health concern,” says Dr Asimakopoulou.

Professor Gibson agrees and raises the issue of progression, where DH becomes more bothersome for patients: “What's going to happen when that patient later has progression and the illness career really takes hold? They're going to look back at that dentist, who didn't hold that conversation, very unfavourably.”

“I think DH provides an opportunity for dentists to be associated with success in behaviour change.”

Sensitivity means success

Changing the way DH is perceived, from an inconsequential, mild condition, to a chronic complaint that can have a significant impact on patients’ quality of life, presents the dentist with an opportunity to engage with the patient and be associated with an easy behaviour change success.

Not only can this help patients manage the problem better but can also enhance the dentist-patient relationship in both the immediate and long-term.